Peak Star Types

Jed Rembold

February 6, 2025

Announcements

- I’m aiming to get HW1 feedback to you this weekend

- Be working on HW2!

- Don’t forget the check-in form this weekend! Make sure you have touched base with your partner and have a plan!

Recap

- Atomic energy levels result in emission or absorption spectra

- Exact levels depend on chemical composition

- Hot diffuse gases emit, colder gases absorb

- Movement towards or away from us shifts our perceived wavelengths

- Redshifted (longer wavelength) going away from us

- Blueshifted (shorter wavelengths) coming toward us

Today’s Plan

- Peak Data Reduction

- Luminosity

- Stellar Distances

- Star Types

- HR Diagrams

Finding and Measuring Absorption Peaks

Maximum Redshift

- Stars are considered “hypervelocity stars” if they have radial speeds of around 500 km/s or higher

- Take a moment to compute how much of a shift this would cause in the \(H_\alpha\) line usually at 656.464 nm.

\[\Delta\lambda = \frac{500\times10^3}{3\times10^8}\times 656.464 = 1.094\]

- The shift would be only a single nanometer!

- Finding the peaks isn’t difficult, as they are largely where we expect

- Measuring the slight differences is far more tricky

Gaussians

- Measure peak placement precisely involves fitting a model to the peak

- One of the most common is that of a Gaussian: \[ g(x) = H +

A\exp\left(\frac{-(x-x_0)^2}{2\sigma^2}\right) \] where

- \(H\) is the offset or shift of the baseline

- \(A\) is the peak height above the baseline (can be negative)

- \(x_0\) is the \(x\) at which the peak is centered

- \(\sigma\) is the spread of the peak

The Continuum

- Peaks often show up on areas of the blackbody spectrum that are heavily sloped

- Fitting them well requires “flattening”, or normalizing out this background continuum

- Most common approach is to fit a line or polynomial to just the background (not the peak!) and then divide the entire background by this signal

- If done well, you should get a clean peak sitting on a level surface, ready for fitting

- For velocities or identifying chemical composition, determining \(x_0\) is the most important, as that is the wavelength the peak is centered at

Example Using Solar Spectra

- To illustrate this approach, let’s investigate the \(H_\alpha\) line in the solar spectra given here

- Want to:

- Establish there is a peak approximately where we expect it

- Normalize the background

- Fit a gaussian to determine peak location

Velocity Computing

- You can technically compute a velocity for each peak individually

- The spectrum will generally have many peaks

- Don’t just average them! Fit a line to them: \[\lambda_{obs} = \left(\frac{V}{c} + 1\right)\lambda_{rest} \]

Luminosity

So what can we observe?

- Light from the stars tells us:

- Their location in the sky

- Their overall brightness

- Their intensity at different wavelengths (their spectrum)

- From these, we can determine:

- Surface temperature

- Radial motion

- Distance (sometimes)

- Size (in a fashion)

- Power output or Luminosity

- Mass (sometimes)

Luminosity

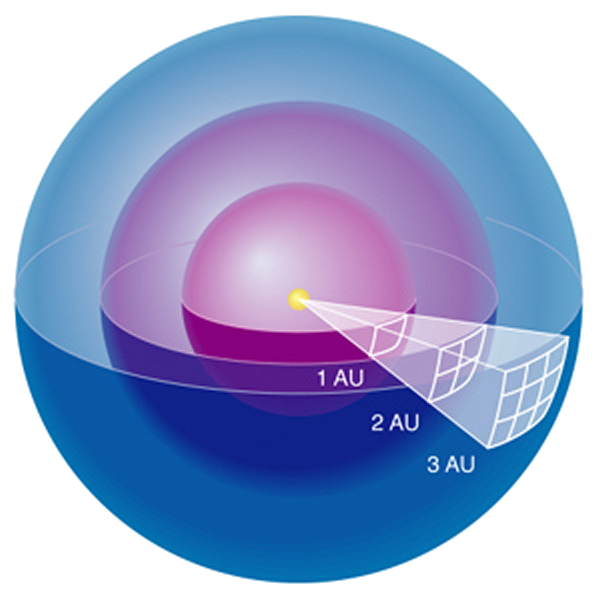

- We measure the apparent brightness \(B\) of an object here at Earth (area under spectra)

- Like ripples around a dropped rock though, brightness falls off with

distance:

- Unlike pond ripples, the waves spread out radially, so the energy gets spread over a sphere

- Thus the luminosity is: \[ L = 4\pi d^2 \times B \] where \(d\) is the distance

- The range of possible stellar luminosities is huge

- \(L_{sun} = L_\odot = 4 \times 10^{26}\) W

- Dimmest at around \(0.000001L_\odot\)

- Brightest around \(100000L_\odot\)

Accounting for Distance

Stellar Distances

- Initially, coming from parallax

- Shifts of the foreground relative to the background when the viewpoint changes

- Parallax effects are larger for closer objects, and stars are

far away

- Need as large a baseline as possible: observing during 6 month intervals to be on opposite sides of the Sun

- Parallax effects from stars are still tiny: generally less than an arcsecond

- A parsec is the distance that corresponds to a parallax

angle of 1 arcsecond

- Equivalent to 3.26 light-years, or 3.26\(\times\) the distance light travels in a year

- Measuring the parallax angle \(p\) in arcseconds gives the distance in parsecs \(d\): \[ d_{pc} = \frac{1}{p_{asec}} \]

Absolute Magnitude

- Astronomers will also use absolute magnitude as a proxy for luminosity

- A star’s absolute magnitude (commonly denoted \(M\)) is the magnitude it would seem to have if it was 10 parsecs away

- Still requires knowing the distance to the star to compute: \[ m - M = 5\log_{10}\left(\frac{d_{pc}}{10}\right) \] where \[ \begin{aligned} M &= \text{ absolute magnitude} \\ m &= \text{ apparent magnitude} \\ d_{pc} &= \text{ distance in pc}\\ \end{aligned} \]

Classifying Stars

Star Types

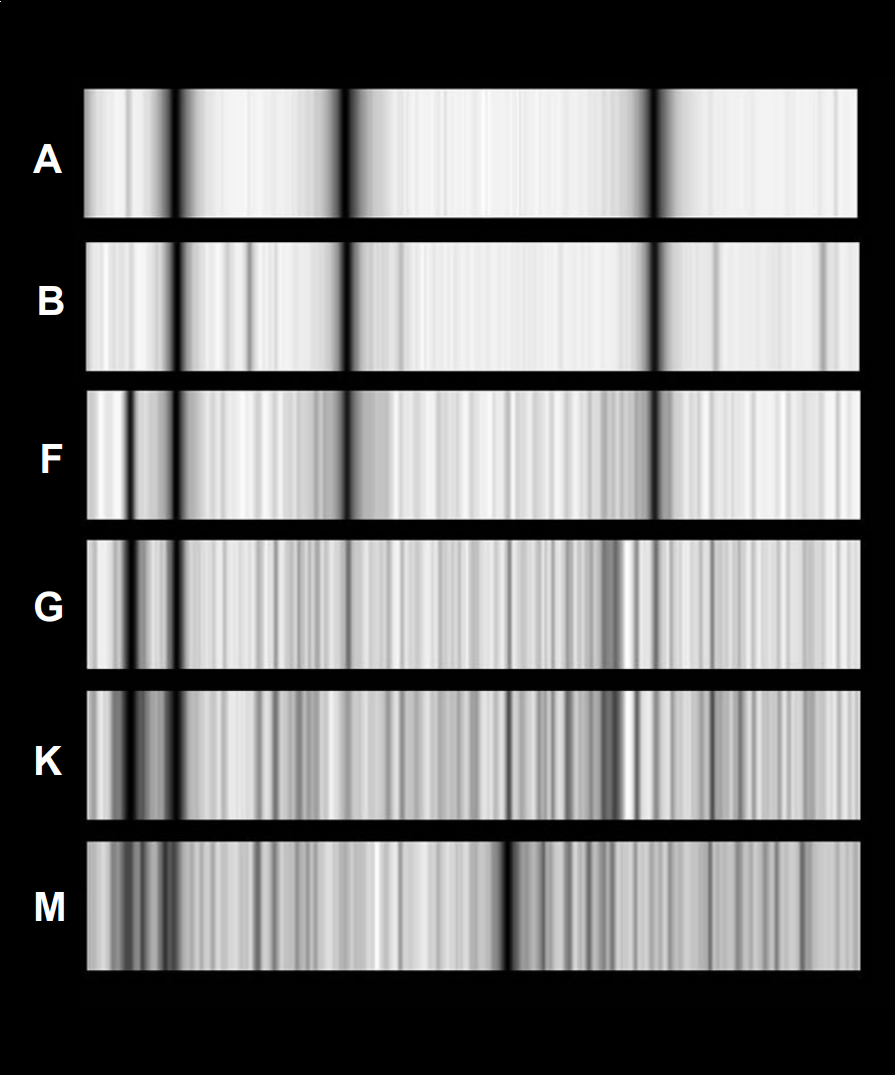

- Stars were originally classified by the strength of their Hydrogen lines

- The strongest were classified type A, all the way down to type O, which showed virtually no hydrogen lines

Scrambling the System

- As more spectra were observed, the H lines were proving to be less reliable in predicting similar properties

- Enter Annie Cannon

- Hired as one of the Harvard Computers

- Classified some 350,000 stars (yikes!)

- Drastically simplied the system and eliminated many classes, focusing mainly on the Balmer line transitions

- Once the relationship between spectra lines and temperature was understood, the letters were reordered to match the temperature trend

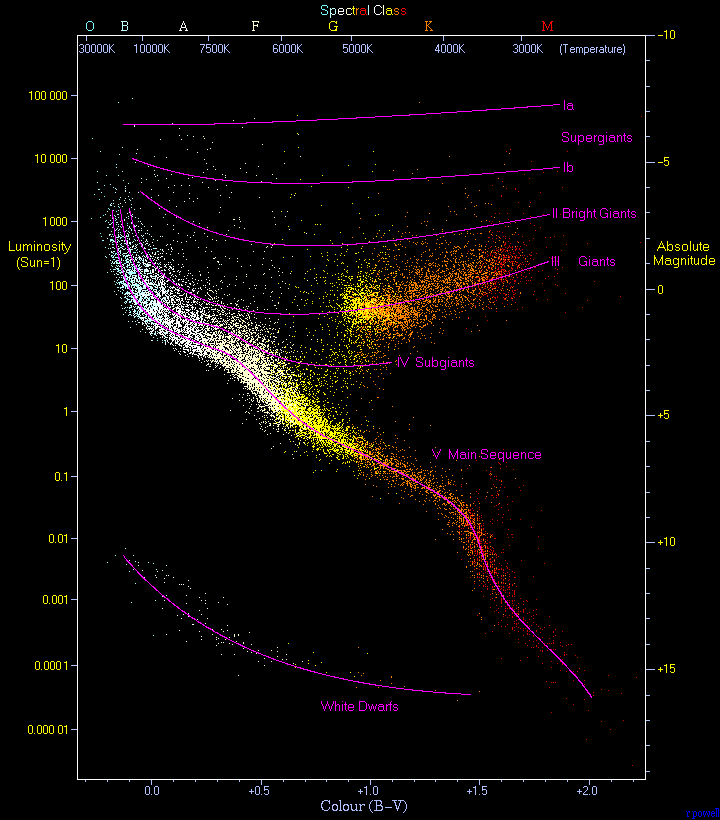

HR Diagrams

HR Diagram

HR Trends

Star Sizes

- Given certain names, you can perhaps guess how stellar size varies in an HR diagram

- But why?

- Recall that total brightness over some interval of wavelength is

measured in watts per square meter

- This would be the area under a spectra curve

- This is why brightness drops off as it travels away from the star to us

- This also means though that the total energy emitted from the surface of the star will depend on the star’s size!

- The area under the curve depends (heavily) on the temperature \[ L = 4\pi R^2_s \times \sigma T^4 \]

- Recall that total brightness over some interval of wavelength is

measured in watts per square meter

Size Trends

- The total energy output of the star thus depends on both its size (radius) and its temperature

- Cooler stars need to be much larger to have the same luminosity output!

- Hot stars can be smaller

Mass and HR Diagrams

- What about patterns in the mass of stars on the HR diagram?

- Globally, there is no obvious trend

- There do appear to be trends within the subgroups

though:

- Main sequence stars decrease in mass from upper left to lower right

- White dwarfs are generally fairly low in mass

- Giants and supergiants can vary wildly

- Mass determines many of the equilibrium points in stars, so no clear trend is interesting!